The “Reed Amendment” and Admissibility to the United States: Will I Be Barred From Reentry After Renunciation?

By Daniel P. Joyce on August 27, 2015 Posted in SmarterWaystoCross.com

A common concern about renunciation of U.S. citizenship is that of admissibility to the United States thereafter. Many people tell me that they have read about a permanent ban on reentry to the United States following renunciation.

There is no automatic ban on reentry following renunciation. (Renunciations must be made outside the United States, typically at a U.S. consulate.) There is a provision of the law that justifies the concern, but an understanding of that law will reveal why there is very little to worry about.

One of the consequences of renunciation of citizenship is the conversion of one’s immigration status from citizen to “alien.” Nowhere is the stark reality of that conversion more apparent than at the border during one’s first attempt to reenter as a visitor. Many former citizens continue to have friends, relative or even seasonal vacation property in the United States, and return visits are not unusual. Without U.S. citizenship, the alien no longer has the right to enter the U.S. and there are no presumptions in his/her favor. For the first time, the newly converted alien must prove that he/she is a legitimate visitor (not intending to live or work in the United States) and that he/she is admissible.

There are many grounds of inadmissibility to the United States contained in section 212 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), ranging from criminal convictions, prior immigration violations, terrorism, public health concerns, and others. Tacked on to the end of section 212, in subsection 212(a)(10)(E), is a curious provision often referred to as the “Reed Amendment” after the congressman who proposed it. The measure was a legislative reaction (many would say overreaction) to a billionaire named Kenneth Dart, who renounced his U.S. citizenship in 1994 and moved to Belize. It was apparent that Mr. Dart was doing so to limit U.S. income tax liability. The case received media attention that happened to coincide with movements in Congress to strengthen the immigration laws regarding illegal immigration and the tax laws regarding treatment of “expatriates.”

Twenty years ago, renunciations were less frequent than today. In the mid-1990’s there were only a few hundred renunciations annually worldwide. A New York Times article from 1995 estimated that “a dozen or more of those who [renounced annually] are multimillionaires.”

The Reed Amendment was aimed at those multimillionaires. It gained enough bipartisan support to be enacted as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. The measure in its entirety states:

Any alien who is a former citizen of the United States who officially renounces United States citizenship and who is determined by the Attorney General to have renounced United States citizenship for the purpose of avoiding taxation by the United States is inadmissible.

Passage of the measure was its high-water mark because its history since that time has been marked by ineffectiveness and disuse. The executive branch never issued implementing regulations, and in 2002, the attorney general’s authority to make the tax avoidance determination was transferred to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). At that time, six years after the law’s enactment, not one person had ever been excluded from entry to the United States for renouncing citizenship for tax avoidance purposes. The same is true today. To our knowledge, the DHS has never made a formal determination of inadmissibility under INA §212(a)(10)(E).

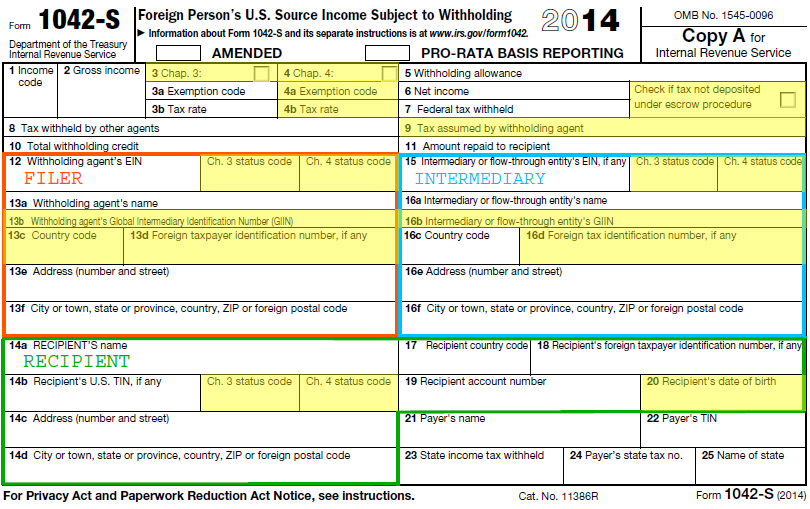

In 2003, the Staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation issued a report to Congress on the “Tax and Immigration Treatment of Relinquishment of Citizenship and Termination of Long-Term Residency,” which explained the “operational complications” involved in implementing the Reed Amendment. At the heart of the problem was the need for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to share information with DHS and other agencies to facilitate a determination of tax avoidance. However, tax information is highly confidential. Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §6103(a)(3) prohibits IRS employees from disclosing “any return or return information” to any other person or agency unless permitted under the statute. There was, and still is, no such provision to allow the sharing of tax return information with DHS for Reed Amendment purposes, and neither the IRS or DHS has promulgated any implementing regulations to make it happen. Accordingly, there currently are no procedures in effect to implement the law.

In 2014, there were 3,415 renunciations worldwide, which was a 13 percent increase over the previous year and close to ten times the average number of annual renunciations in the mid-1990’s. And the trend is upward: There were more than 1,000 renunciations in the fourth calendar quarter of 2014 alone. There have been at least 15,000 renunciations since the passage of the Reed Amendment in 1996—many of whom can be presumed to be multimillionaires—but no reported case during that time of a finding of inadmissibility for tax avoidance purposes.

The consular officer does not collect any tax information at the renunciation appointment and does not make a determination, or even a recommendation, concerning future admissibility. The renunciation process does not require the applicant to state a reason for renouncing. Unless the applicant decides to volunteer such information, the application is devoid of any express statement regarding the person’s motivation for renouncing. We generally advise against making such a voluntary statement.

The prudent former citizen would be careful about making any inflammatory comments about the U.S. tax system or taxes in general, whether at the consulate or at the border. It is within the authority of the inspecting Customs and Border Protection officer at the border to make a finding of inadmissibility on any of the grounds contained in INA §212. During the inspection process, a person’s place of birth or prior U.S. citizenship may give rise to questions about nationality, because a U.S. citizen is required by statute to claim U.S. nationality and present a U.S. passport. Someone who has renounced citizenship need only present a copy of the Certificate of Loss of Nationality to confirm that he/she is no longer a U.S. citizen. No explanation or reason is required or recommended. Despite its disuse, the Reed Amendment is still a valid law and therefore has the potential for use and misuse, even in the absence of the formal determination contemplated by its terms. For obvious reasons, the inspection booth during entry to the U.S. is neither the time nor the place to make political statements or constructive criticisms of the U.S. tax system.